Applications of Systems Thinking – Systems Thinking Framework

The world of today is complicated and changing quickly, making old linear and reductionist methods of problem-solving inadequate.

All types of organizations deal with dynamic issues including climate change, structural racism, public health crises, and interruptions to global supply systems, which don’t have simple answers or solutions.

These types of systemic issues involve many interdependent components and forces that generate unpredictable effects over time.

Systems thinking provides a different lens – one that allows us to grasp the bigger picture, see the interconnections, and better anticipate intended consequences.

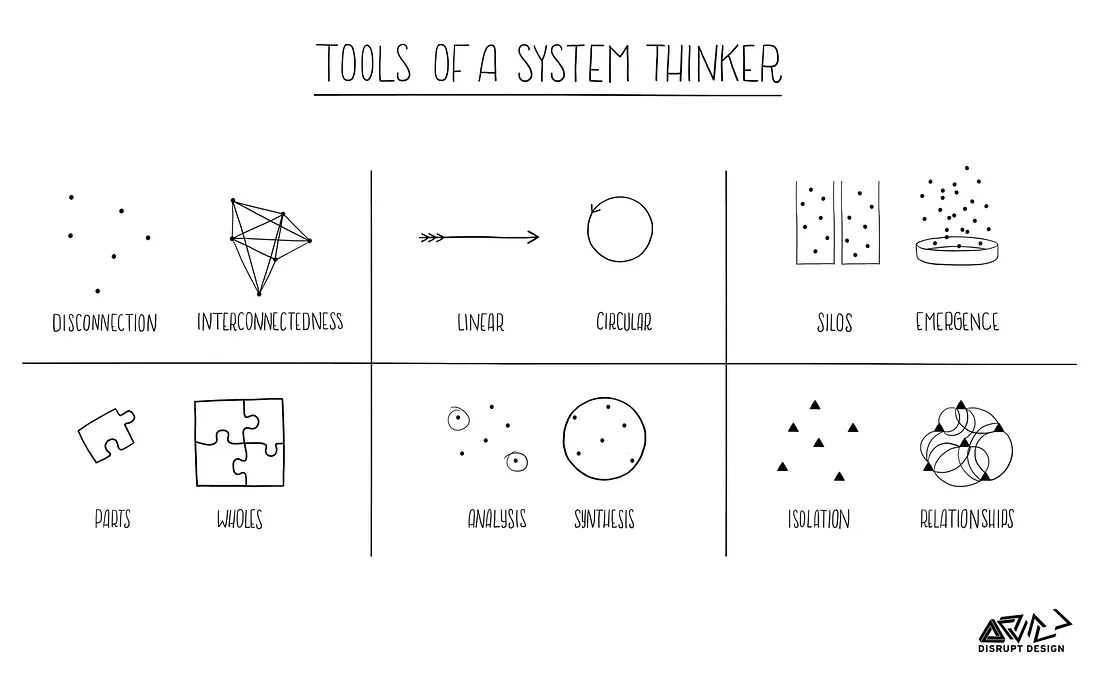

A systems thinking framework looks at relationships, perspectives, boundaries, and the whole, rather than just events or isolated parts. It is an extremely useful approach for tackling “wicked problems” and enabling more holistic solutions.

By cultivating a deeper understanding of systemic structures and behaviors, you’ll be better equipped to solve complex problems and catalyze positive change – whether at the organizational or societal level.

The goal is to introduce you to systems thinking principles you can apply to enhance decision-making, adaptability, and collaboration skills – critical capabilities for navigating today’s messy, nonlinear challenges.

With some foundational knowledge and the right frameworks, anyone can adopt systems thinking tools to help foster sustained learning and impact within their teams and organizations over time. So let’s dive in!

What is Systems Thinking?

Systems thinking is a method for comprehending how elements interact to form a whole system. By analyzing the connections and interactions between the many components that make up a system, systems thinking aims to comprehend systems holistically.

The notion that a system’s constituent elements may behave differently when separated from the system’s surroundings or other elements is fundamental to systems theory.

Systems thinking focuses on how a change in one area may influence other areas and how systems self-correct over time via feedback, as opposed to only examining isolated occurrences within a system.

The foundation of systems thinking rests on several key principles:

Foundations & Key Principles of Systems Thinking

The concept of holism argues that systems need to be seen as cohesive wholes rather than as a mere assembly of pieces.

The whole exceeds the sum of its constituent components.

Understanding the entire system and the fundamental relationships between its components that give rise to systemic behaviors is the goal of systems thinking.

A core focus is on relationships between parts of a system rather than the parts in isolation. These relationships generate interconnections and interdependencies which are important for understanding dynamic complexity.

Perspective emphasizes that individuals have their lenses for interpreting complex situations based on their knowledge, experiences, and values.

Incorporating diverse perspectives is critical for gaining insight into different systemic forces.

Examining system boundaries involves looking at which elements are inside or outside of the system and determining the appropriate breadth to define the system for a given purpose.

Defining clear system boundaries establishes the scope of what is being studied in the broader environment.

Core Concepts of Systems Thinking Framework

Systems thinking draws upon several foundational concepts for understanding complexity:

Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) are made up of several parts that change and develop over time. Because they are dynamically evolving, complex systems demonstrate nonlinear behaviors making them difficult to predict.

Examples of complex adaptive systems include the human immune system, an ant colony, the global economy, and climate.

Feedback Loops refer to situations where an initial change leads to impacts upon the system that eventually come back to cause additional change to the original element.

There are two types – reinforcing feedback that amplifies change and balancing feedback that counteracts change. The effects of feedback loops typically happen over varied time delays.

Dynamics & Emergent Properties relate to the behaviors that arise over time through the interactions of various agents and influences within a complex system.

Small changes can sometimes foster unanticipated emergent results. It is difficult to understand emergent properties by only examining system parts rather than observing the system holistically.

Mental Models describe people’s internal belief systems about how parts of the world work. They shape how we interpret problems and opportunities.

By examining our mental models and those of others, we can identify flawed assumptions or areas of disagreement that may limit shared understanding of complex situations.

These interrelated concepts underscore why systems behave in nonlinear and unpredictable ways. By studying patterns and interrelationships, systems thinking aims to anticipate potential impacts of changes over varying timelines.

This equips decision-makers to plan more thoughtfully.

Key Systems Thinking Frameworks

There are a variety of useful systems thinking frameworks and associated models. These tools create scaffolding for diagnosing issues, mapping complex systems, and analyzing dynamics and patterns over time.

Two foundational examples are Senge’s Five Disciplines model and the Iceberg Model.

Iceberg Model

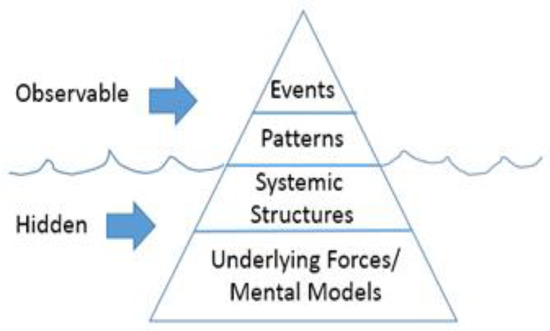

The Iceberg Model serves as an important metaphor for what we see or observe versus the influential yet often hidden drivers of systemic issues.

Similar to an iceberg floating in water, only about 10% of its total mass is visible above the surface, while 90% of an iceberg’s bulk and shape lies unseen underwater.

In the systems thinking iceberg model, “events” represent visible, often sudden problems or incidences that capture attention.

However, a systems thinking approach tries to understand what lies beneath the symptoms by diving down the iceberg.

“Patterns” refer to trends, sequences, and behaviors over time – that is how and why events keep recurring. By studying patterns we can begin anticipating and getting ahead of issues rather than just reacting.

“System structures” make up the conditions that shape behavioral patterns within a given group, organization, or society such as policies, procedures, physical characteristics, and relationships between components.

System structures causally affect patterns of behavior within the system.

At the base of the iceberg are “mental models” operating as the taken-for-granted beliefs and assumptions that justify and reinforce particular structures and policies that may not be working well or serving stated goals.

By re-examining prevailing mindsets, we can identify needed shifts to enact substantive and sustainable change.

Senge’s Five Disciplines

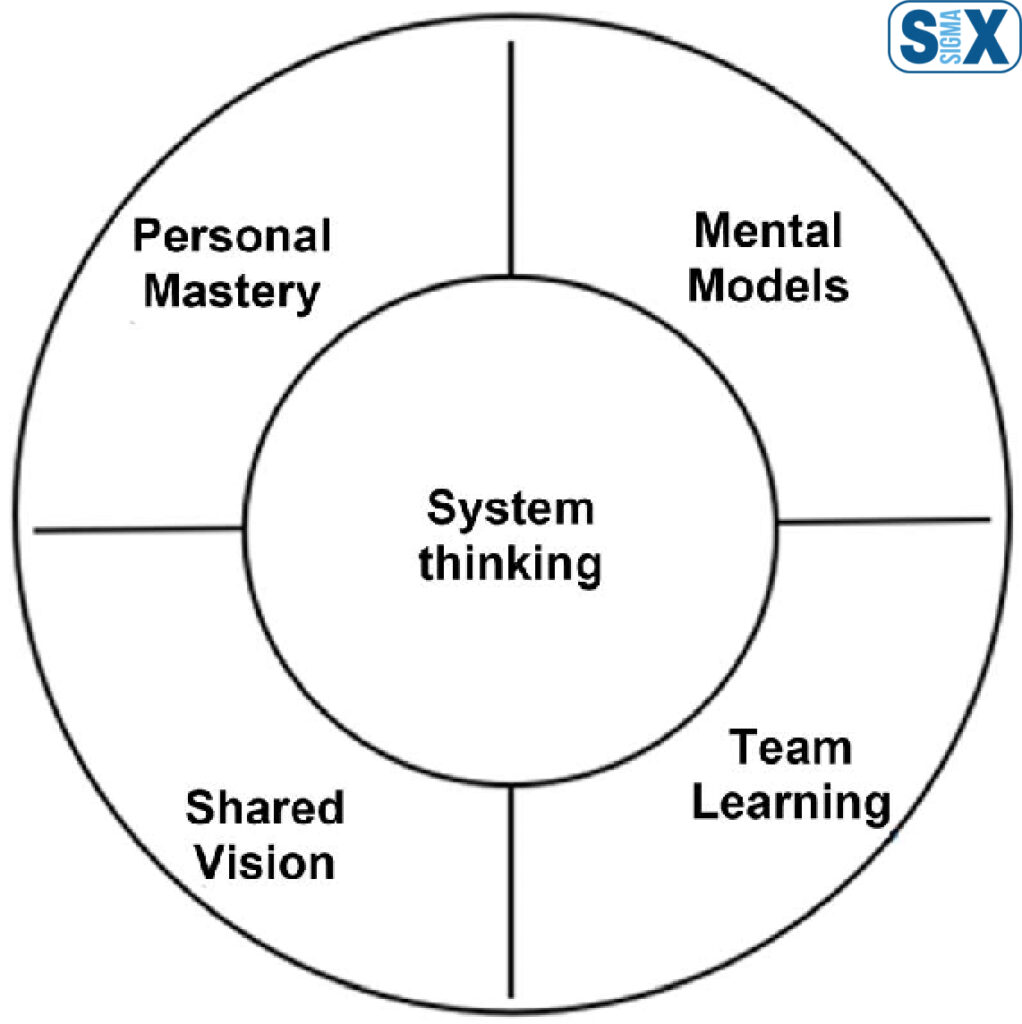

Peter Senge outlined an approach oriented toward organizational learning called the Five Disciplines model centered around systems thinking.

Each discipline builds skills needed for effectively analyzing complexity and catalyzing change:

Systems Thinking is the cornerstone discipline focused on recognizing interdependencies and changing behavior arising from system structures.

It allows seeing interconnected systems from multiple levels and perspectives, beyond simple cause-effect relations.

Personal Mastery emphasizes continually clarifying and deepening personal vision, purpose, and understanding the current reality more clearly.

It’s about fostering a lifelong commitment to learning and acquiring expertise.

Mental Models involve reflecting on internal assumptions and generalizations that influence how we comprehend the world.

By unearthing mental models, we can identify areas that limit our understanding to better integrate divergent perspectives.

Shared Vision cultivates building a sense of group commitment through developing images of a desired future state that fosters energy and enrollment rather than compliance.

A shared vision aligned with guiding ideas and shared purpose can provide focus and priority for systems-level change.

Team Learning happens through teams come together to think insightfully about complex issues. Aligned with systems thinking techniques, team learning builds skills in openly sharing views to allow insights not attainable individually.

It leverages collective wisdom for collaborative problem-solving and is a vital capacity for enabling change within systems.

Together these mutually reinforcing disciplines encourage thinking more systemically to perceive increasingly complex forces of change while being mindfully embedded in collective learning journeys.

Applying Systems Thinking

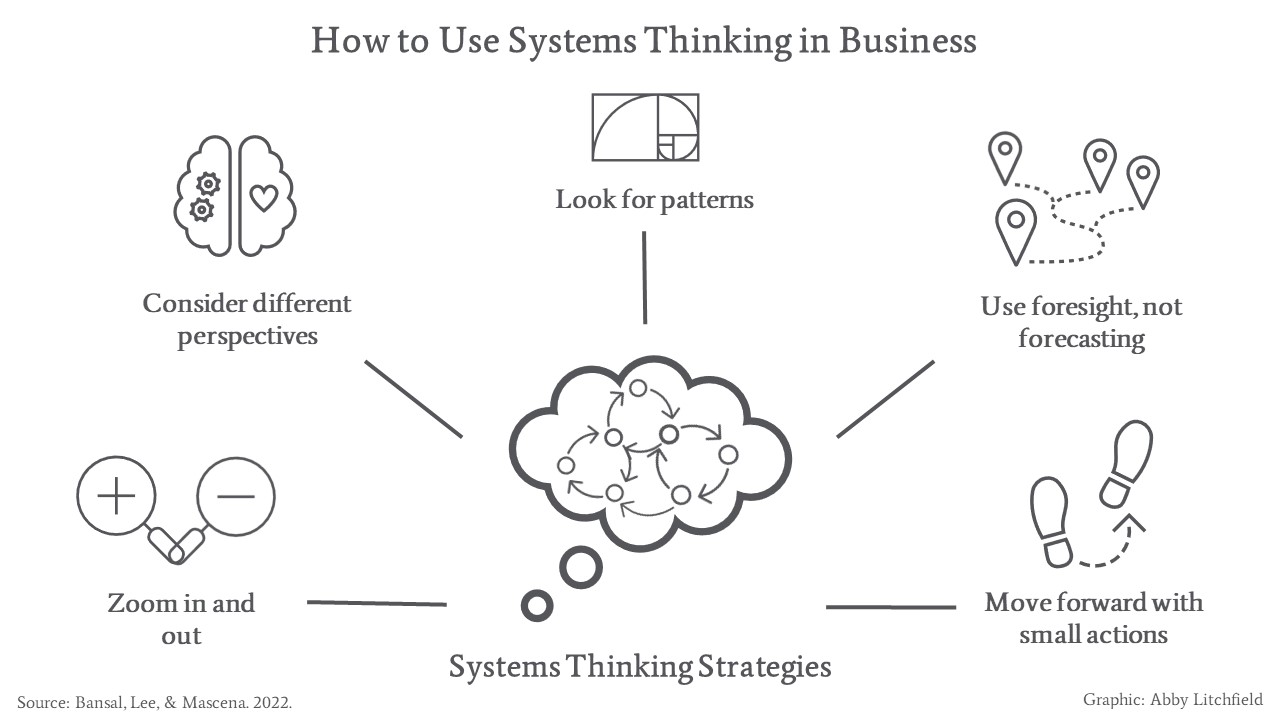

While systems thinking represents more of an overall mindset than a rigid methodology, there is a general process that can be followed to apply systems concepts for gaining insight into complex issues.

Conducting a systems analysis involves key steps for defining system scope, mapping interconnections, diagnosing patterns, and identifying leverage points for change.

Steps for Systems Analysis

The first phase of systems analysis starts by establishing the foundation – agreeing on the boundaries, components, and dynamics that comprise the system being studied.

This requires identifying key variables and clarifying the perspectives of various actors. Next is systematically mapping the relationships between elements to see reinforcing and balancing processes playing out over time.

The goal is to create working theories for what mechanisms may be producing both the presenting symptoms and root causes.

Finally, potential high-impact interventions aimed at shifting dynamics are considered for scenario analysis and decision-making evaluations.

Various qualitative and computational tools can be used within a systems analysis depending on the purpose and scope, which will be covered later in this guide.

However, most applications follow these foundational steps to approach complex issues more systematically rather than reactively.

Defining the System & Boundary

Clearly defining the system boundary provides orientation for the scope under examination.

This involves determining which elements and relationships are most relevant for the inquiry and which are outside the current focus.

System boundaries can be expanded or contracted as needed to hone understanding over time.

Clarifying objectives, mapping all stakeholders, and discussing individual perspectives make system boundaries more obvious.

Stakeholder analysis identifies who is impacted within the system, directly and indirectly, and each stakeholder group’s interests.

Gathering multiple subjective interpretations of the situation enriches the systems analysis and helps ensure important variables don’t get overlooked.

In some cases, it works well to create visual maps of the system showing nodes and potential links to represent components and relationships.

This further defines connections between parts and essential flows within the bounded system.

The goal is to establish the landscape in focus – elements to be studied intently through a systems thinking lens.

Understanding Connections

After determining the scope of analysis, systems thinking aims to map connections between parts of the system to identify closed chains of causal relationships called feedback loops.

By tracing cause and effect over time, we can uncover virtuous or vicious cycles along with unintended consequences.

Reinforcing feedback loops depict self-perpetuating cycles that amplify or accelerate changes flowing through them. The effects build on themselves driving more growth.

However, uncontrolled escalation typically leads to a breakdown somewhere.

Balancing feedback loops counteract change and promote stability within a system.

Also called goal-seeking loops, they attempt to achieve an equilibrium state via self-correction in response to deviations. Delays often moderate the corrective impact.

In complex systems with many interdependent balancing and reinforcing loops, behavior arises that remains challenging to anticipate.

Time delays between cause and effect introduce additional turbulence. Actions can have delayed impacts that come back to cause trouble later if temporal effects are not considered.

By conceptualizing the myriad interrelationships tied by intricate feedback processes over time, a causal loop diagram provides a powerful visual means for seeing systemic forces.

The goal is to identify leverage points within loops where strategic interventions may shift dynamics toward more desirable outcomes.

Diagnosing Dynamics

As feedback loops interact, they generate dynamic patterns of behavior over time.

Systems thinking tries to diagnose the underlying structures driving observed patterns and events to identify promising intervention points.

Systems archetypes reveal common recurring cycles of behavior using a set of generic structures. These fundamental patterns like “fixes that fail” or “limits to growth” appear across various contexts.

Recognizing systemic archetypes provides a shortcut to rapidly understanding what self-reinforcing or self-correcting processes may be perpetuating a problematic situation.

Leverage points indicate places within complex systems where a solution element can be introduced to transform system behavior to a more optimal state with the least amount of effort.

The identification of high-leverage interventions is crucial for avoiding wasted efforts and unintended consequences.

There are varying levels of leverage ranging from the ability to fully transcend paradigms down to more concrete details like altering feedback loops.

By uncovering mental models, discovering influential leverage points comes more quickly. This analytic stage is challenging as it requires synthesizing interrelated forces that aren’t necessarily obvious.

Taking time for reflection and divergent input sets the stage for finding innovative, pivotal solutions.

Systems Thinking in Organizations

Systems thinking has extensive applications across government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and companies for informing strategy and catalyzing change.

Reasons why groups formally integrate systems methods include:

Addressing Wicked Problems

Complex challenges like climate change, public health crises, or regional instability that involve multi-causal forces with no simple policy solution require analysis tools beyond linear causality.

Systems thinking helps groups better unpack the subsystems, mental models, and leverage points related to such persistent issues.

Facilitating Organizational Learning

Embedding systems thinking methodologies across departments enhances learning capabilities helping organizations see beyond events to patterns shaping performance over time.

This cultivates data-driven analysis, informed hypotheses of root issues, and strategic responses.

Tackling Root Causes

The interrelated frameworks and mapping tools within systems thinking reveal underlying structures driving observable events.

This allows targeting transformational change toward root causes rather than just reacting to symptoms.

Building Shared Understanding

Participatory modeling sessions convene diverse experts and leaders to jointly map out complex domains.

This builds alignment around key variables and interdependencies within an ecosystem’s dynamics.

Different mental models surfaced through structured dialogue.

Enabling Adaptive Change

In a world of growing uncertainty, systems thinking capabilities increase organizational resilience, agility, and responsiveness amid turbulence.

Running simulations of plausible scenarios allows for discovering novel solutions and future-proofing decisions.

The common thread is using systems thinking to perceive deeper drivers shaping current realities and possible alternatives to inform wise action.

Putting it Into Practice

While adopting a systems thinking perspective represents a fundamental mindset shift, there are also many conceptual tools used to map and model complex domains.

As systems thinking is increasingly applied through both private and public institutions, useful skillsets bridge theory, analysis, synthesis, and application.

Learning & Applying Tools

Concept Maps visually depict relationships between key components within a system using labeled arrows to denote directional links.

These simple causal diagrams extract the most critical variables and convey interconnections. Concept maps provide a starting point for bigger-picture analysis.

Behavior Over Time Graphs reveals how key variables change over time. By studying historical patterns and oscillations, future dynamics can be anticipated more accurately.

These time-series depictions quickly communicate what trends exist.

Stock & Flow Models enable building computer simulations using differential equations to quantitatively represent accumulation and drainage rates affecting systemic variables.

Critical numbers get estimated even with uncertainty to assess impacts over time.

System Archetypes apply generic structures to quickly diagnose common dynamics observed across various contexts like “fixes that backfire” or “accidental adversaries.”

By recognizing familiar patterns, appropriate interventions become clearer.

These tools can be used in a complementary fashion to support one another, enrich perspective, and build consensus on what dynamics may be driving issues.

Developing a Systems Mindset

While systems analysis relies on conceptual tools, cultivating a systems thinking mindset represents the ultimate competency.

A system thinking approach sees relationships rather than linear cause-effect chains and recognizes patterns over time rather than single events.

Developing systems thinking integrates critical and creative thinking skills with the habits of connecting the dots, seeking multiple perspectives, and continually synthesizing information.

Systems thinkers tolerate ambiguity for a time resisting narrow or reactive conclusions until deeper drivers come into focus.

This capacity sharpens by practicing reflection through journaling, dialoguing in groups, and mapping out one’s mental models.

Over time, systems thinking habits help anticipate whole system behaviors, gauge change holistically and perceive nuances and interdependencies missed by others.

Benefits of Systems Thinking

There are many advantages both individually and organizationally to applying a systems thinking perspective:

The Big Picture

Synthesizing across siloed issues and specialized experts, systems thinking provides a framework for rising above events and details to integrate key patterns, drivers, and relationships.

This leads to wiser interventions.

Anticipating Unintended Consequences

By tracing multiple pathways of direct and indirect effects, potential negative outcomes get identified earlier preventing reactive risk mitigation.

Cross-disciplinary analysis enriches foresight.

Promoting Collaborative Change

Uncovering mental models and fostering a shared understanding of complex dynamics leads groups past polarization toward integrated solutions.

Embracing a learning posture opens the possibility of transformational thinking.

Developing systems thinking know-how pays dividends through enhanced context, coordination, and collective intelligence when addressing multidimensional challenges.

Overcoming Barriers to Systems Thinking

While a systems thinking approach delivers many benefits, transforming group norms and leadership practices aligned to mechanistic ways of operating often meets resistance.

Shifting time horizons from immediate outcomes to long-term patterns counters many status quo structures.

Common obstacles arise but can be mitigated by senior commitment, capacity building, and new success measures.

Common Barriers

Linear Cause-Effect Thinking

Habits of simplistic analysis seek single culprits for issues and direct solutions rather than accommodating dynamic complexity. This tends to generate policy resistance and recurring issues.

Parts vs. Whole

Holistic thinking sees interdependencies while reductionist perspectives oversimplify by isolating events and elements losing context. Stove-piped metrics and planning likewise need integration.

Focus on Quick Fixes

Incentives driving short-term results undermine investing time upfront to map deeper structures needing long-term transformation. Quick solutions usually fail or cause more issues.

Lack of Collaboration

Participatory modeling and shared learning are central to systems thinking, yet many groups lack protocols for constructive dialogue, surfacing assumptions, and synthesizing perspectives.

While adopting systems thinking may necessitate structural and cultural changes, the demonstratable benefits motivate persistence through typical barriers.

Cultivating a Systems Culture

Installing new frameworks is easiest when the organizational conditions cultivate openness, creativity, and collective discovery.

Typical command-and-control management limits success. Leaders seeking to incubate systems thinking should nurture a learning ecosystem marked by:

Fostering Curiosity

Inquiry starts by suspending assumptions and asking why complex challenges persist. Curiosity about root causes and seeking divergent data sources light the spark for analysis.

Encouraging Reflection

Creative and critical thinking skills allow seeing reality from alternative perspectives. Journaling, discussing in pairs, and mapping mental models builds capacity.

Promoting Critical Thinking

Examining premises and evaluating contexts counters narrow views. Welcoming scrutiny of reasoning patterns makes theories more robust. Leadership modeling this permission gives cover.

Building Trust & Psychological Safety

Vulnerability underpins breakthroughs but requires risk-taking. Teams won’t expose ignorance or disagree unless trust exists. Safe space for thinking aloud takes continual nurturing.

With the right foundation emphasizing trust, transparency, learning, and questioning – systems thinking tools gain adoption more readily leading to collective growth.

Using Systems Tools & Models

Systems thinking represents a broad paradigm encompassing a range of frameworks, methodologies, and modeling techniques.

While a key goal centers on mindset transformation related to seeing interdependencies, relationships, and patterns – conceptual tools add rigor and provide scaffolds for analysis.

Models also enable simulations for testing decisions and policies.

Causal Loop Diagrams

Causal loop diagrams offer a fundamental visual language for representing the feedback loops and delays governing dynamic complexity.

By explicitly mapping variables connected by arrows denoting causal links, closed loops emerge showing reinforcing or balancing cycles of influence.

Carefully constructed causal loop diagrams allow quick grasping of the systemic structures generating observed patterns over time.

Key steps when facilitating a causal loop diagramming session involve first establishing the priority question, framing key variables, and determining scope.

Then through iterative dialogue and questioning, primary causal relationships get drawn to form key feedback loops. Loops get labeled to convey the type of influence they exhibit over time.

Validation happens through group reflection and storytelling – tracing round loops to describe the dynamic hypotheses.

Causal loop mapping provides a foundational framework for tackling multidimensional problems plaguing leadership teams.

The participatory process builds shared mental models, systems thinking skills, and commitment to address root dynamics rather than just reacting to events.

Stock & Flow Models

While causal loop diagrams effectively map feedback relationships qualitatively, adding quantitation enables building computer simulations.

Stock and flow modeling leverages system dynamics principles to mathematically represent accumulation and drainage rates affecting key variables within a complex system.

Steps include:

- Identifying key stocks (accumulations)

- Defining inflows increasing stocks

- Specifying outflows decreasing stocks

- Mapping supporting variables connected to flow rates

- Estimating relationship coefficients between variables

- Assembling into the simulation model

Once constructed, the computational model gets initialized, parameters tuned, and tests run replicating historical patterns.

With increased confidence in model validity, simulations reassess policies or forecast the impacts of new decisions by examining behavior over time. Experiments compare tradeoffs.

The benefits of quantitative modeling and simulation include consolidating dispersed knowledge, testing assumptions, building consensus, and creating management flight simulators for evaluating many scenarios.

Quantified system behavior yields insights not possible with conceptual mapping alone particularly over long time horizons. It does require adding numbers to relationships.

Participatory Modeling

While system dynamics modeling aims to capture complex interdependencies, the process of collaborative mapping and simulation building proves equally valuable.

Often called group model building, participatory modeling convenes diverse experts and leaders to jointly conceptualize fuzzy issues, weigh tradeoffs, and test prospective solutions.

As groups walk through model conceptualization, eliciting variables, and quantifying relationships – mental model gaps surface while clarity increases.

Facilitated sessions support constructive debate, surfacing assumptions for revaluation, questioning inferences, and integrating across disciplines. Through shared efforts, systems thinking skills diffuse.

Since flawed mental models often drive suboptimal policies, group model building allows reexamining perceptions to the bigger picture.

Simulated experiments provide low-risk environments for evaluating ideas and shifting stubborn viewpoints. Interpreting outputs elicits discoveries.

Ultimately the capacity built for joint learning, trust building, reaching shared understanding, and informed decision making continue benefiting organizations long after initial insights get implemented.

Participatory modeling incubates systems thinkers.

Systems Thinking in Action

While systems thinking emerged from fields like biology, engineering, and physics – systems thinking frameworks and methodologies now see wide enterprise adoption for tackling complex business problems.

Areas of focus span strategic planning, risk analysis, program management, process improvement, and leading organizational change.

Business & Organizations

Problem-solving & Strategy Development

Approaching multifaceted challenges like product innovation, entering new markets, or crisis scenarios through a systems thinking lens reveals insights traditional SWOT analysis misses.

Simulating future scenarios allows the discovery of robust strategies.

Supply Chain Optimization

Understanding interdependencies between partners, producers, distributors, etc. allows for strengthening resilience to demand volatility, shortages, transport issues, and evolving customer needs – especially when augmented by interactive modeling.

Organizational Learning & Change Management

Leveraging frameworks like Senge’s five disciplines to transform group culture, processes, and mindsets centered on systems thinking breeds the agility and experimentation needed for organizations to learn and thrive through disruption.

The common thread centers on leveraging systems tools to enhance perception, alignment, and decision-making capabilities to outperform competition.

This systems approach is driving innovation across industries.

Systems Thinking in Healthcare & Social Systems

Systems thinking offers great promise for improving population health outcomes and informing public policy given multifaceted challenges like obesity, substance abuse, chronic diseases, health equity, and pandemic preparedness centralize complex human and institutional behaviors.

Addressing Complex Public Health Issues

Factors span biology, lifestyle, socioeconomics, built infrastructure, access to care, cultural norms, and politics. Systems tools unpack cross-sector influences.

Informing Policy Decisions

Modeling proposed programs provides decision support to compare scenarios, augment limited data, anticipate side effects, reveal cost factors, and guide resource allocation.

Facilitating Collaborative Action

Multi-stakeholder engagement convenes diverse advocates to foster a shared understanding of root causes versus symptoms and coordinated interventions across health, transportation, environment, business, education, etc.

While progress takes time given bureaucracy and politics, the overdue modernization of public health infrastructure to utilize systems thinking is gaining support through demonstrating effectiveness with vexing medical and social dilemmas.

International Development

Applying systems thinking to complex challenges like poverty, hunger, gender equity, responsible economic growth, climate resilience, improving infrastructure, and reducing conflict/violence is gaining traction across programs in developing countries. Benefits include:

Understanding Interconnections

Holistic assessments reveal how health, education, economic, ecological, and sociopolitical dimensions interconnect when evaluating needs and designing interventions.

Anticipating Unintended Consequences

Multi-year simulations modeling systemic impacts of new policies or partnerships prevent adverse effects through more inclusive analysis spanning outcomes like skills development, technological capabilities, agricultural capacity, population dynamics, and governance capacities.

Enable Adaptive Management

Shared learning and participatory modeling build capabilities within regional teams for continually evaluating conditions to adapt programs aligned to societal goals as circumstances evolve.

A systemic approach increases effectiveness over time by focusing investments at the highest leverage points informed through technology-enabled analysis, community engagement, public-private collaborations, field expertise, and development science.

Getting Started with Systems Thinking

For leaders and change agents wanting to apply systems thinking to tackle difficult problems and coordinate collective impact, adopting a few foundational practices provides scaffolding for success before diving into advanced tools.

Rather than getting overwhelmed by complexity, a systematic approach allows growth in competency over time.

Where to Begin

Defining Your System

Clarify the purpose, scope, and boundaries around the complex issue to be addressed by leveraging stakeholder input. Frame the priority question and build an initial variable list.

Identifying Key Relationships

Discuss potential connections between variables and subsystems. Map assumptions of causal links and feedback loops with small groups via whiteboards or sticky notes.

Recognizing Perspectives

Gather diverse experts and those impacted to enrich understanding. Capture different interpretations, concerns, and mental models related to the situation through dialogue. Allow assumptions to surface.

These basic steps invite broader input for enhanced clarity surrounding complex circumstances to determine appropriate next steps amid uncertainty.

The practices build habits for thinking more systemically about problems while structuring group learning essential for progress.

Next Steps

Apply Systems Tools

Use conceptual mapping to articulate interconnections. Introduce simulation models to quantify potential impacts. Learn analytics for evaluating complex networks. Build visual literacy.

Foster Collaborative Analysis

Convene workshops for participatory modeling, shared debriefs of insights, and developing dynamic hypotheses of root issues. Deepen external partnerships.

Take Small Actions

Enhance feedback channels. Adjust key parameters incrementally. Embed pilot studies to generate real-world data. Value progress through experiments.

Keep Learning & Adapting

Reassess system boundaries over time. Grow knowledge through research. Visit other organizations utilizing systems methods. Give updated data inputs to models.

Rather than tackling monumental change, systems thinking promotes an iterative approach of incremental enhancements informed by new insights from deliberate learning cycles.

As capabilities advance, more intricate tools get incorporated.

SixSigma.us offers both Live Virtual classes as well as Online Self-Paced training. Most option includes access to the same great Master Black Belt instructors that teach our World Class in-person sessions. Sign-up today!

Virtual Classroom Training Programs Self-Paced Online Training Programs